Maturation is a biologically universal phenomenon, as is the notion of a developmental transition. How this transition is structured and understood varies according to culture (Sigelman & Rider, 2006). Adolescence, as understood in the Western sense, begins with the changes brought on by puberty and culminates in the acquisition of adult roles and responsibilities. This includes the formation of a personal and social identity and the discovery of moral purpose. The consensus view from the fields of neuroscience, developmental psychology and sociology is that the ‘adolescent transition’ begins as early as 10 years old and continues into the mid-twenties.

Adolescence is not a uniform process but a dynamic period of development characterised by rapid change. The following domains have been identified as central to these changes by the NSW Centre for the Advancement of Adolescent Health and the Transcultural Mental Health Centre (2008):

- Physical – onset of puberty (physical growth, development of secondary sexual characteristics and reproductive capability)

- Psychological – development of autonomy, independent identity and a value system

- Cognitive – moving from concrete to abstract thought

- Emotional – moodiness; shifting from self-centredness to empathy in relationships

- Social – peer group influences, formation of intimate relationships, decisions about future vocation

No single theory or model of development provides a truly universal construct for understanding the changes that young people will undergo in the transition to adulthood. The elucidation of forces shaping young people’s development and the patterns that it typically follows has given rise to a generalised model of “normative” adolescent development. Melbourne-based anthropologist David Moore (2002) recommends being suspicious of “…universalising, ideological statements about the archetypal ‘adolescent’, animated by internal drives, that require careful handling and engaged in the search for a fixed personal identity” (p49).

Conceptualising development as normative has been critiqued for the inadequate consideration given to changes occurring within the broader social and economic environment. Kilmartin (2000) points out that the idea of normative development remains based on traditional pathways such as moving from school to work, leaving home, establishing a relationship, getting married, purchasing a home and having children.

The power inherent in the social divisions of society is also underplayed. Wyn and White (1997) found that “…social change has both costs and benefits that are not evenly distributed or confined to particular groups of young people” (p15). Further criticisms centre on a failure to take into account cultural and religious differences among young people (Sigelman & Rider, 2006) and a tendency to masculinise adolescence (Gilligan, 1982).

While acknowledging the validity of this critique, it is generally accepted that young people must undertake a range of developmental tasks to successfully negotiate the adolescent transition.

The NSW Centre for the Advancement of Adolescent Health and Transcultural Mental Health Centre (2008) provide the following list of tasks:

- Achieving independence from parents and other adults

- Developing a realistic, stable, positive self-identity

- Forming a sexual identity

- Negotiating peer and intimate relationships

- Development of a realistic body image

- Formulation of their own moral/value system

- Acquisition of skills for future economic independence

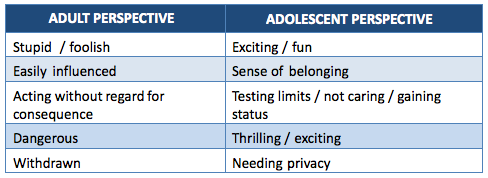

To achieve developmental tasks, young people must take risks and learn through experience. The risks young people take and the way they behave on their developmental journey can only be understood in light of the gains they hope to make. Young people need the space, support and experience to develop the necessary capabilities to eventually take responsibility for their own safety, health and well-being. Adolescent perspectives and motivations are likely to differ from adults. Table 1 offers simple examples of alternative explanations that either adults (care givers) or young people may have to explain typical adolescent behaviour.

Source: Bruun and Palmer (1998).

At times, young people expect or yearn for the structure, support and nurturing that was available to them as a child, even though they will almost always be reluctant to admit it.

Young people require support, guidance, modelling and teaching from others in the course of their development. They also require appropriate discipline and monitoring from caring adults. This role is typically performed by parents or legal guardians, who must constantly consider the capacities of the young person and set relevant limits to regulate their exposure to risk. Limits are most often set around behaviours that are believed to compromise the safety, health and future prospects of the young person.

Young people often complain about the limits that are set for them as they naturally desire more responsibility for decision-making than their parents or guardians are prepared to give. Even so, the setting of limits linked with fair consequences provides structure and a sense of containment as well as a clear set of rules that young people can test out and define themselves against.